B"H

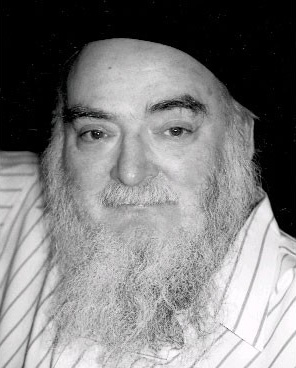

Reb Mordechai ben Reb Shaul Staiman

Memorial page

<> This page is under construction

<>

Reb Mordechai ben Reb Shaul Staiman o.b.m.

It is with tremendous pain and sorrow that we made this "memorial page"

in the loving memory of our dear friend and copy editor, Reb Mordechai ben

Reb Shaul Staiman, who passed away, on Tuesday, 22 Tamuz, 5763 (July 22,

2003).

Reb Mordechai Staiman was a very kind person, who gave tirelessly from

his time and effort for the success of our organization "Torah Publications

For The Blind," and this publication "Living With Moshiach" in

particular.

Reb Mordechai Staiman has been a prolific writer, editor, publicist,

and copywriter for over thirty nine years. His articles have appeared in

many publications including, The Jewish Press, Wellsprings,

The Algemeiner Journal, N'Shei Chabad, Beis Moshiach,

Chabad, Country Yossi Family Magazine, and L'Chaim.

He also published 5 books.

He will be dearly missed by all very much.

May his memory be a blessing for us all.

-

NIGGUN: Stories behind the Chasidic Songs

that Inspire Jews (1994)

-

Waiting for the Messiah: Stories to Inspire Jews With Hope (1996)

-

Diamonds Of The Rebbe (1998)

-

Secrets of the Rebbe that Led to the Fall of the Soviet Union (2001)

-

His Name Is Aaron and other amazing Chassidic Stories and songs. Includes

story of the escape of the Previous Lubavitcher Rebbe from World War

II, Germany. (2002)

To order the books, in the USA call: 1-877-505-7700, of go to: Mitzvahland

- One Stop Judaica Shop, at:

http://www.mitzvahland.com

In his own words

-

Once Upon A Pain - Reprinted from

L'Chaim issue #140 (20 Kislev 5751 - Dec. 7, 1990)

Friends writting about him

-

Did Reb Mordechai Staiman inspire you?

-

Did you enjoy reading his writtings?

Please send to us your stories about Reb Mordechai Staiman, you can e-mail

them to Rabbi Yosef Y. Shagalov

(A never before published article, written

(in January 1997) by Reb Mordechai Staiman)

"Who is blind?" a Ladino writer once asked. His answer: "He who declines

to see the light."

Thank Hashem, chasidim of the Rebbe have been seeing the light

for almost 47 years, and can't wait till the ultimate light arrives with

Moshiach. Yet for years one Lubavitcher chasid named Rabbi Yosef Y.

Shagalov was bothered about something. Over and over, he used to wonder:

"What about the blind and the hard of seeing? They're certainly not

declining to see the light. There must be something I can do. But what?"

Suddenly it was no longer a brain-solving problem. The solution had hands

and feet. In his sichos, on Shabbos Parshas

Eikev, 5751, the Rebbe further lit up the path to the Redemption,

by announcing that the publication of the Tanya was printed in (Hebrew)

braille. Now, the way was open, for spreading the teachings of

Chasidus, to people who never before had the opportunity to taste

this spiritual knowledge, in a new window for the soul.

And just as quickly, Rabbi Yosef Shagalov, taking his cue from the Rebbe,

sprang spiritedly to his own feet and let his fingers do the talking on his

computer.

Out of this emerged one of the most important Lubavitcher publications,

Living With Moshiach, ever to hit the Orthodox Jewish market. The

weekly magazine, which is generally 16 pages long but has hit the "newsstands"

with 64 pages, has a twofold purpose: 1) to keep the visually impaired and

the blind up to date on Moshiach matters, and, by doing so, 2) help hasten

his arrival, as the Rebbe himself has encouraged all of us to do many times.

The "newsstands" that Shagalov reached were the libraries for the visually

impaired and blind all over the U.S. and its worldwide territorial possessions.

And due to the generosity of certain benefactors, the magazine also reaches,

free of charge, thousands of blind and handicapped Jews, public service libraries

and nonprofit organizations, and countless others also via the Internet.

As for the publication itself, a breakdown of its material, culled from many

chasidic sources, as printed in L'Chaim Weekly Magazine, shows a definite

emphasis on the teachings of the Rebbe.

It all began with the sending out to the blind and visually impaired a Happy

New Year's Card for 5753, with the Rebbe's message, printed in large, 22

point type and also in braille. This was then followed up by four 9" by 12"

holiday magazines issues, under the banner: "Moshiach -- Holiday Series."

These included Moshiach and Chanukah, Moshiach and Yud Shevat,

Moshiach and Tu B'Shevat and Moshiach and Chof Beis B'Shevat,

all 64 pages long.

At the same time Rabbi Shagalov printed these issues for the

visually impaired, he joined forces with Rabbi Menachem

Sheingarten, who used his braille machine to publish the issues for the totally

blind.

It was an exciting time for the two rabbis, for so many reasons, because,

as it says in Living With Moshiach as well as many other places, "It

is our fervent hope that our learning about Moshiach and the Redemption will

hasten the coming of Moshiach, Now!"

One of the most thrilling yet almost frustrating moments came on the night

of Kislev 19, 5753, when, if you recall, the Rebbe, recovering slowly

from his stroke, made an appearance -- although appearance is not

the right word for this ecstatic occasion -- for six hours at a

farbrengen in 770. That night all of Crown Heights seemed much brighter

and hopeful. And on that same night, two chasidim -- Rabbi Shagalov

and this writer -- were laboring to prepare the first "blind" issue for the

printer the next morning -- and willing to give their right arm (only kidding

of course, but it's a good expression to stress their urge) to be with the

Rebbe. Imagine: six hours of basking in the Rebbe's light! What a gift! Yet

time was of the essence, and if we didn't finish tonight -- and it looked

as if we'd be working long through the night -- we could just forget about

the Chanukah issue and our new readers. We'd have to start all over next

holiday, with different material.

So, finally, what did we do? The Rebbe's ways and means won the day -- or,

in this case, the night. Here we were trying to follow his directives, to

spread Yiddishkeit to the blind. Surely, if we asked the Rebbe what

we should do now on this very night, to come to see him in 770 or to spread

the wellsprings of Chasidus in doing what we were doing, there was

no question what the Rebbe would want us to do. So we remained at our

"drawing-board," editing and editing, until the wee hours in the morning

(try seven or eight a.m.), and the publishing of our first issue was, thank

G-d, a big success. Letters from Jews immediately started coming in from

around the nation, thanking us for reaching them in their remote places and

bringing a lot more than a bit of Chasidus to their lives. They were

so happy that other Jews cared enough to reach out to them. The same elation

and gratitude were expressed at the "770" Chanukah rally, sponsored by Kolel

Tferes Zkeinim -- Levi Yitzchok, the Lubavitch Torah Institute for seniors,

headed by Rabbi Menachem Gerlitsky. At the rally, each elderly man and woman

was presented with a free copy of Moshiach and Chanukah.

Then, as with all smooth-running machines, a glitch finally came up. Rabbi

Sheingarten moved, lock, stock and barrel, including the braille machine,

with his family to Buenos Aires to become the Rebbe's sheliach there.

But this did not deter Shagalov's determination one bit. So, until he could

come up with about $20,000 to buy his own braille machine, Shagalov, soon

thereafter, began to print a small (in size) weekly magazine, about, as we

mentioned earlier, 16 to 64 pages long. This is the Living With Moshiach

series he now spends many sleepless nights producing (besides holding

down a full-time job during the days). So far he's put out, under the auspices

of the Lubavitch Shluchim Conferences on the Moshiach Campaign, Committee

for the Blind, more than 90 issues. It all began at the urging at the

Shluchim's convention of 1992. There, one of the resolutions called

for publication of Moshiach written material for the blind and the visually

impaired.

Suiting the action to the word, the magazines issues took hold, and what

issues they were! Even non-Jews were impressed. One case quickly comes to

mind. As part of the labor-of-love task of mailing off the issues, Shagalov,

one night a week, delivers his ready-to-mail bags of booklets to the post

office. One night he was approached by an elderly black female postal worker.

In her hand was a copy of the previous week's issue of Living With

Moshiach.

"Rabbi, Rabbi," she excitedly asked Shagalov, "where can I get this every

week?" The lady's eyes were very moist as she looked at Shagalov.

"Why?" he sincerely asked her.

"Because, in it, you have the holy words of G-d!"

From then on, Shagalov left some copies at the post office for the postal

workers to read.

A typical issue will contain the weekly Torah portion, adapted from the works

of the Rebbe; Maimonides' Twelfth Principle of Faith; the Rebbe's Prophecy

about Moshiach and the Redemption; times for candle-lighting, or where to

phone for further info; ads about the "Good Card" and "Moshiach In The Air"

radio and TV programs; the Rebbe's call to action, like, for example, enrolling

your child in a Torah summer camp; many highly interesting and relevant subjects;

and, of course, the Rebbe's photograph.

"What a joy it is to open a magazine such as yours and see the beaming face

of the Rebbe. I feel all lit up each time I see him," is the typical response

in letters by visually impaired readers.

Many of his magazines revolve around specific holidays. Shagalov goes to

great pains to produce -- ah! if he only had the money and time to produce

a 120-page issue every week, he'd do it -- the most compact Moshiach issue

he can produce in 18 point type. "It's not easy," he smiles, knowing that

he has to be realistic; he can't write a tome every issue on one subject.

But he tries, he really does. And his work pays off in many ways.

The week after Chanukah 5755, about 4 in the morning, a Jewish male postal

worker approached Shagalov at, where else but the post office, and said,

with a feeling heart, "Rabbi, your Chanukah issue was unbelievable. All my

life I never knew the complete story of Chanukah. Never had a proper Jewish

education, but your magazine feeds me, and I guess I've been starving for

information most of my life as a Jew. So, G-d bless you and your organization."

And the letters keep coming in, according to Shagalov. "You know you're making

it big-time," he said, "when you receive a letter, which I did this past

March, from an eye doctor in a faraway state. He wrote to tell me that somebody

showed him one of my magazines and he would like to subscribe, in order for

his patients to read it in his waiting room. Nu, nu, when you

can get your Living With Moshiach magazine in waiting rooms of doctors,

to me, that's big-time."

Yet, Shagalov is the first to admit, it's often a struggle to get out each

weekly issue on time, although you'd never know it by his almost heroic pluck.

As soon as Shagalov is ready to print his magazine, donors are rarely on

his doorstep, begging to pay for the printing costs of each and every issue

So, the man who deeply loves his Rebbe, and believes "with complete faith

in the arrival of Moshiach," has to wear many hats to get the job done. "I

do what I have to do," says Shagalov. Of course, he wishes more financial

supporters would remember this great cause, promoted and endorsed by the

Rebbe, and help finance the magazine's production. One rewarding way this

can easily be done, Shagalov points out, is for a donor to pay for a particular

issue, thereby dedicating it to himself, his family or a recently departed

loved one. Address all correspondence to: Enlightenment For The Blind, Inc.

602 N. Orange Drive. Los Angeles, CA 90036 USA. [or via

email, or via the Internet, at the

"Enlightenment For The

Blind, Inc OnLine Donation Page"]

During one of those long nights putting out Living With Moshiach,

this writer turned to Shagalov and asked: "Yossi, how come you devote so

much of your life, waking and sleeping, to the Rebbe's Moshiach Campaign?"

"I'll tell you," he said.

Shagalov's personal history itself reveals part of the answer. His grandfather

was Rabbi Yitzchok Elchonon

Halevi Shagalov, the previous Rebbe's sheliach in Gomel, Russia,

who was brutally murdered by Stalin's henchmen for carrying out the previous

Rebbe's directive to spread Yiddishkeit throughout Russia.

"How come I devote all my life to this great cause?" the 38-year-old

Shagalov said to me. "Because the Rebbe prophesied that

'The time of our Redemption has arrived!' and

'Moshiach is on his way!' And Because I won't do any less than my

grandfather. The apple doesn't fall far from the tree. All his life he pushed

Yiddishkeit; all my life I'll do everything I can to hasten Moshiach."

So, now, who is blind? Clearly not the readers of Living With Moshiach!

By Rabbi Alexander Zushe Kohn(1)

"Mordechai the Jew... sought the good of his people and spoke for the

welfare of all of his seed." I can think of no more succinct description

of Reb Mordechai Staiman o.b.m. than this verse from the Book of Esther.

Like the legendary Mordechai of Shushan, Mordechai Staiman sought to inspire

Jews with a love for their heritage and their people. That's why he wrote

Niggun, a book about the power of Jewish song, and that's why he wrote

Diamonds of the Rebbe, a book about famous Jewish personalities whom

the Lubavitcher Rebbe inspired to greater spiritual achievement. Waiting

for the Messiah tells the story of our people's yearning for the Redemption,

and Secrets of the Rebbe describes how Chabad's Mesirus Nefesh

activities on behalf of Russian Jewry led to the fall of the Soviet Empire.

Mordechai's last masterpiece is called His Name is Aaron, and its

amazing stories will warm even the iciest of hearts with the fire of Chassidism.

Mordechai saw himself as an emissary of the Lubavitcher Rebbe in every sense

of the word. Instead of using his unique writing skills to create a New

York Times bestseller -- which he could have a done on a Monday afternoon

-- he devoted himself to bringing the joy of Judaism and Chassidism to as

many Jews as possible. In addition to his Jewish bestsellers, Mordechai sent

numerous articles to many Jewish publications, copyedited all editions of

the weekly Living with Moshiach digest (for the blind and visually

impaired) for free, edited Chassidic Stories Made In Heaven,

prepared a rough draft of a Moshiach encyclopedia, and, for a number

of years, proofread L'Chaim weekly.

Mordechai once related how on the night of Yud-Tes Kislev, 5753, when

the Rebbe appeared on the balcony for six consecutive hours, he and his friend,

Rabbi Yosef Y. Shagalov were laboring to prepare the first "blind" Chanukah

issue for the printer the next morning. The temptation to go and bask in

the Rebbe's light was very powerful. But they didn't go, because Mordechai

maintained the Rebbe would tell them to sacrifice their noble aspirations

for the sake of another Jew -- all the more so for the sake of many Jews,

some of whom would be learning about Chanukah, and about Chassidism, and

about Moshiach for the first time in their lives.

"Even the Gentiles liked him," notes a close friend of the Staimans. "He

would say nice things to people whom you and I would be afraid to talk to,

and this generated an atmosphere of peace between the Jews on the block and

their gentile neighbors."

Mordechai was forever trying to make people smile. When I first met him,

a decade ago, he cracked some good humored jokes with me, and for the next

ten years he didn't stop. This was especially amazing considering that Mordechai

suffered his own fare share of pain, and could easily justify being miserable.

I remember visiting him at home after his heart surgery. The minute I

saw him, I could tell that he was in a lot of pain. He whispered that

he can't really talk because he's very weak. Then he said, "One minute,

I'll be right back." He went into a back room and emerged with pad and

paper in hand. He then proceeded to interview me -- not without managing

a few good-hearted wisecracks in-between questions -- about a subject he

was planning to write about in one of his upcoming books.

So, the next time you think of Reb Mordechai Staiman, go ahead and make a

Jew smile; tell a Jew a Chassidic story; sing a Jew a Niggun. And

if you don't know how, let Mordechai himself do it for you. For though Mordechai

will be sorely missed, "he has left us the writings," (to paraphrase

the fifth Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Sholom DovBer, at the time of his passing),

which will continue to inspire Jews all over, until the last page of history

has been written.

*

A web site has been established in the loving memory and also featuring the

works of Reb Mordechai Staiman, o.b.m. You can find it at:

https://torah4blind.org/staiman

_______________

1. Rabbi Alexander Zushe Kohn is the founder of

"myChassidus.com" Spreading the

Wellsprings Further. He can be reached at:

info@mychassidus.com, or at

718-419-8757.

Reprinted from L'Chaim issue #140

(20 Kislev 5751 - Dec. 7, 1990)

When storytellers gather at a Shabbat dinner, candle lights flicker

and the whole world dances in the shadows. This happened to me once,

unimportantly, when I was in extreme physical pain from recent lower-back

surgery. Who wanted to hear -- who could hear -- stories! I had had enough

of them, all beginning with "Once upon a pain..."

Yet, here I was, my wife and I, at the beginning of another Shabbat,

in the company of a family of Lubavitch storytellers. The hosts and guests

took their seats. I waited till the last moment to sit. Doubts that I should

have ventured out in the first place, notwithstanding the Shabbat,

added to the pain in my back and right leg. Would I be able to sit for more

than a few minutes at a time? How was I going to make kiddush, standing,

when I could hardly hold myself together let alone hold a brimming cup of

wine in my right hand and a prayer book in my left? How successfully, with

newly self-taught Hebrew rushing around in my head, would I carry out my

determination to read everything in Hebrew? How was anything I had to say

or hear that night going to be sufficiently removed from my surgery and pain

to make me forget myself and remember G-d?

But the candle lights flickered, we blessed our washed hands and the

challa, and the meal began. There were tales of the Baal Shem Tov,

of course, and mention of Rebbe Israel, the Maggid of Kozhenitz, who

was so weak he had to be carried to services for more than 15 years and who

regained his strength only when he prayed, singing and dancing feverishly,

his body well again -- just for that time.

I didn't come to hear that. My pain never seemed to go away. Then, too,

surrounded by the hosts' sons, I really wanted my own son seated next to

me and my wife at the table. So I closed my eyes and went looking for my

21-year-old son Ari, who lived in Japan and seemed very far away from Judaism.

[Ed. note: Ari means lion in Hebrew]

When I opened my eyes, I suddenly saw on the wall a painting of a man standing

next to a lion. "Who is that?" I asked my host. Smiling, he said, "That is

the cover to my old story, Ariel and the Lion." I enjoined him to tell me

the story.

Ariel had to travel. He joined a caravan upon the condition that they halt

the trek for Shabbat. Agreeing, the guide took Ariel's money, but

when Shabbat arrived, he refused to stop. His excuse was that they

were at the edge of a forest full of cutthroat brigands. Ariel, undaunted,

chose to stay alone there to celebrate the Shabbat and the caravan

departed.

As he prayed, Ariel heard rumblings and felt hot breath on his neck. He looked

up. It was a ferocious lion. There was nothing else to do so he kept on praying.

He prayed, ate, dreamed and celebrated Shabbat -- the lion remaining

where he was all the time. When Shabbat ended, the lion motioned to

Ariel to get on his back. Together they made their way through the forest

until they reached the caravan, that is, the remnants of it. All the travelers

had been beaten and robbed and not much was left of the wagons. With the

lion's help, Ariel arrived at his destination.

I didn't have to ask the significance of it all. My own son, Ari, travelled

some 6000 miles in that moment to tell me. Ariel and the lion. Ari my son,

the lion. G-d had brought me back to Judaism just last year. He'd do the

same for my son Ari, I firmly believed, and for my daughter Lisa, Arielle.

That's why I had to leave my sickbed and come here for the Shabbat

meal: to be delivered; to see a new day. As the Maggid of Kozhenitz

said, "Every man must free himself from Egypt every day."

If you think this story is about forgetting my own pain for a while, perhaps,

it is. But on the way home, my wife, Ada told me about a difficult experience

that one of the storyteller's sons had had recently. Yet that night, at the

Shabbat table, he spoke with such gusto that it was impossible to

know that he was under any ordeal.

"In all things we trust G-d."

Whoever said that said a mouthful. I'm getting around to appreciating that.

Slowly. After all, with G-d's help, I'm leaving Egypt and working my way

toward the Promised Land.

Back to "Living With Moshiach" Home Page

|